He possessed the rarest combination of qualities - he was a most meticulous scholar, and at the same time he was also a brilliant original thinker. He was a man with an exceptional range of knowledge which extended well beyond his own professional field; a bibliophile who spent endless time in exploring the antiquarian bookshops of Europe, and succeeded, twice in his lifetime (first in Italy, and later in England), in building up a unique collection of rare books. And he spoke with equal fluency in at least four languages.

[…]

He had a subtle and very personal wit, the capacity of making wholly unexpected responses to points raised in a discussion, but above all he had the rare gift of being able to inspire his partners in conversation just by listening with shining eyes. He had that enviable quality of making his friends feel at their best in his company - he made them feel cleverer, more clear-sighted, and eloquent (and amusing) than they normally thought themselves to be. Nicholas Kaldor on his friend Piero SraffaFor the better part of 70 years, rumours of a financial coup have followed the Italian economist Piero Sraffa. Long the subject of speculation, it has been asserted that in the dying days of the Second World War, Sraffa heavily bought defaulted Imperial Japanese Government bonds.

Though several authors have offered accounts of Sraffa's activities, until now, nobody has been able to offer a satisfying and granular account of events.

A handful of writers, including the American investor Murray Stahl, have written about Sraffa. Stahl summed up the lack of clarity surrounding the economist in his book How They Did It: Exceptional Stories of Great Investors, by writing:

Though it may seem peculiar that a Cambridge lecturer would spend considerable time and effort speculating in defaulted government securities, there are several observations that may be made.

Piero Sraffa and John Maynard Keynes were friends and colleagues. It seems unlikely that Keynes' investing activities would have escaped Sraffa’s attention. Additionally, as the editor of David Ricardo’s correspondence, Sraffa would have been well acquainted with Ricardo’s own speculations in government bond markets. Moreover, the Imperial Japanese Government bonds in question were the subject of regular commentary in the press of the day. Any diligent reader of the English financial newspapers would have been apprised not only of the debt, but also of the regular flow of information and commentary that was published about it.

Two credible accounts of Sraffa’s investments survive. The first comes from Sraffa's friend, the economist Nicholas Kaldor, who wrote:

Though Sraffa was the son of a prosperous lawyer, he was only able to bring a small part of his father’s fortune out of Italy. He disliked gambling, and was also against speculating on the Stock Market, not so much on principle, as out of a conviction that one is bound to lose on unsuccessful bets a large part of the gains made on successful outcomes. Hence his basic principle was to wait for the one occasion when a large speculative gain appeared to be absolutely certain, and then put all the money one can get hold of on this one gamble.

The one occasion which appeared to him to satisfy these criteria occurred during the War when the price of Japanese bonds fell to a very low level—something between 5–10 per cent of their nominal value, or not more than 1–2 per cent if one also takes the likely value of unpaid interest payments into account. He was convinced that, however the War might end, the Japanese would fulfil all their foreign financial obligations, whether they were made to do it or not.

Hence he put all his money into Japanese bonds, after careful investigation of which most of them appeared undervalued, and he must have made a gain of 40 to 50 times the money he put into it, when, after the War, Japan resumed servicing the bonds and paid the accumulated interest during the years of hostility. It is not known how much money he made on this transaction, but the College valued his bequest at £1.5 million in 1983, one half consisting of the value of his library.The second comes from the historian Norman Stone:

Whilst both accounts are relatively coextensive, neither is dispositive.

Thankfully, recent events, including the opening of Sraffa’s archive at Trinity College, afford new insight in to what Sraffa did, when he did it, and, indeed, how he did it.

Piero Sraffa was many things; none of them boring.

Born in Turin, Italy on the 5th of August 1898, Sraffa was welcomed into a comfortable Italian family. His father, Angelo Sraffa, was a lawyer and Professor of Law until 1916, when he became Rector of the Bocconi University of Milan.

Sraffa graduated in 1920 as a Doctor of Law with a dissertation on the inflation that plagued Italy through the First World War and into the Interwar period. The thesis spoke not only to the history of inflation in Italy, but also to the potential remedies to the inflationary challenges still extant at that time.

In 1921, Sraffa travelled to Britain to attend the London School of Economics from June to August. It was here, with a letter of introduction, that Sraffa first met Keynes whilst visiting Cambridge. Sraffa would return later in the year for another term at the London School of Economics and would again meet with Keynes.

At the time, Keynes was editing a weekly supplement for the Manchester Guardian Commercial on the post war reconstruction of Europe. The two spoke about the state of the Italian banking system, with Keynes asking Sraffa to prepare a paper on the illegal bailout of the Banca di Sconto by the Italian state. However, the paper that Sraffa submitted was deemed unsuitable, as it was too technical, and instead was published as The Bank Crisis in Italy, in The Economic Journal.

The article, published in 1922, surveyed the wreckage of the Banca di Sconto, from its formation through its demise in 1921. Twice, it had tried to shore up its position by merging with a rival, the Banca Commerciale Italiana. Sraffa, who had been well briefed on the affair, disclosed new details that had been assiduously concealed by the Italian press.

In June, 1922, Sraffa found work with the City Administration of Milan organising a labour statistics office. But his term there was to be a short one. When the Fascists seized power in October of that year, he resigned in protest. Around this time, Keynes requested a second article about Italy’s banking problems, this time for the Guardian’s supplement. The article, titled Italian Banking Today, was published in December 1922.

Unlike the first, this second paper was translated into Italian and read by a newly installed Benito Mussolini. Mussolini was incensed by the paper and telegrammed Sraffa’s father to complain. Mussolini accused Sraffa of the ‘sabotage of Italian finance’, issued threats and demanded that Sraffa write a retraction.

No retraction was made. Instead, Angelo Sraffa responded on his son's behalf whilst Piero hastily decamped to Lugano, Switzerland for several days amid speculation of legal proceedings being brought against him.

‘[…] The article in question,’ wrote Angelo Sraffa in reply to Mussolini, ‘is a pure and simple statement of figures and facts publicly known and not contradicted. He has nothing to rectify and nothing to add, and therefore cannot accede to the request to write a second article.’

In 1923, Sraffa secured employment as a lecturer in Public Finance and Political Economy at the University of Perugia. In 1926, he became a Professor of Economics at Cagliari in Sardinia.

In January, 1927, Keynes wrote to Sraffa to extend a rare invitation to lecture at Cambridge. The offer proved irresistible. Fearing the possibility of imprisonment by Mussolini, as had befallen his friend Antonio Gramsci, Sraffa accepted with gratitude and commenced a four year lectureship in October 1927. Whilst there, he became a participant in the ‘Cambridge Circus’ - a group that contemplated the macroeconomic problems of the day and advised Keynes.

By 1930, Sraffa’s mounting unhappiness with his own lectures led him to decide that he would resign his lectureship. Keynes interceded, and instead organised three new jobs for Sraffa. The first, as the librarian of the Marshall Library at Cambridge; the second, as editor of the collected works and correspondence of David Ricardo; and third, as an Assistant Director of Research.

The Collected Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo was finally published, after much delay, beginning in 1951. In 1960, Sraffa published his book Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities. In 1963, Sraffa retired but remained as librarian until 1973.

In 1981, Sraffa experienced a thrombosis and passed on the 3rd of September, 1983 after two years of illness.

He left his entire estate, including his library, to Trinity College.

Following her entry into the Second World War, Japan began to default on most of her external obligations in, as best as can be figured, mid 1941.

At the outbreak of the war, a number of Imperial Japanese Government bonds were listed on the London Stock Exchange. These securities were issued in the United Kingdom, denominated in British Pounds and were obligations that Japan had entered into under British law.

Japan could refuse to acknowledge them, but could not inflate them away, nor strike them out by fiat. And so they remained outstanding, with an ongoing market made, all through the war and into the peace that followed; shielded from the worst problems of the immediate post war Japanese economy by dint of their denomination in sterling and their legal domicile.

Following her 1941 default, the bonds, already on the ropes prior to the war, collapsed completely.

By the end of the war, the situation had not improved.

At the close of 1945, the following bonds were listed on the London Stock Exchange with prices and cumulative defaulted coupons as follows:

| Issue | Price (%) | Unpaid Coupons (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Japan 4% 1899 | 24 | 18 |

| Japan 4% 1910 | 21.5 | 18 |

| Japan 5% 1907 | 26.5 | 22.5 |

| Japan 6% 1924 | 27 | 27 |

| Japan 5.5% 1930 | 31.5 | 24.75 |

| Tokyo 5.5% 1926 | 23 | 24.75 |

| Tokyo 5% 1912 | 19.5 | 22.5 |

Modelled with £100 face value.

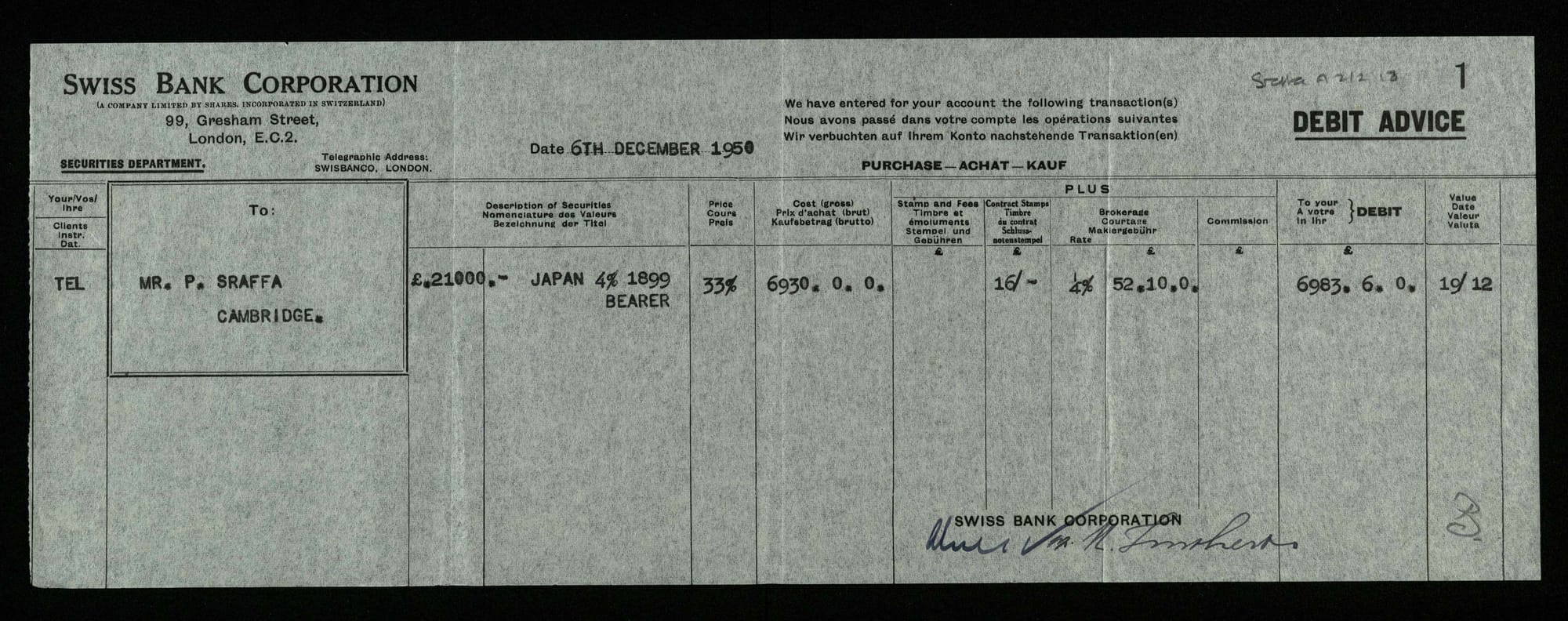

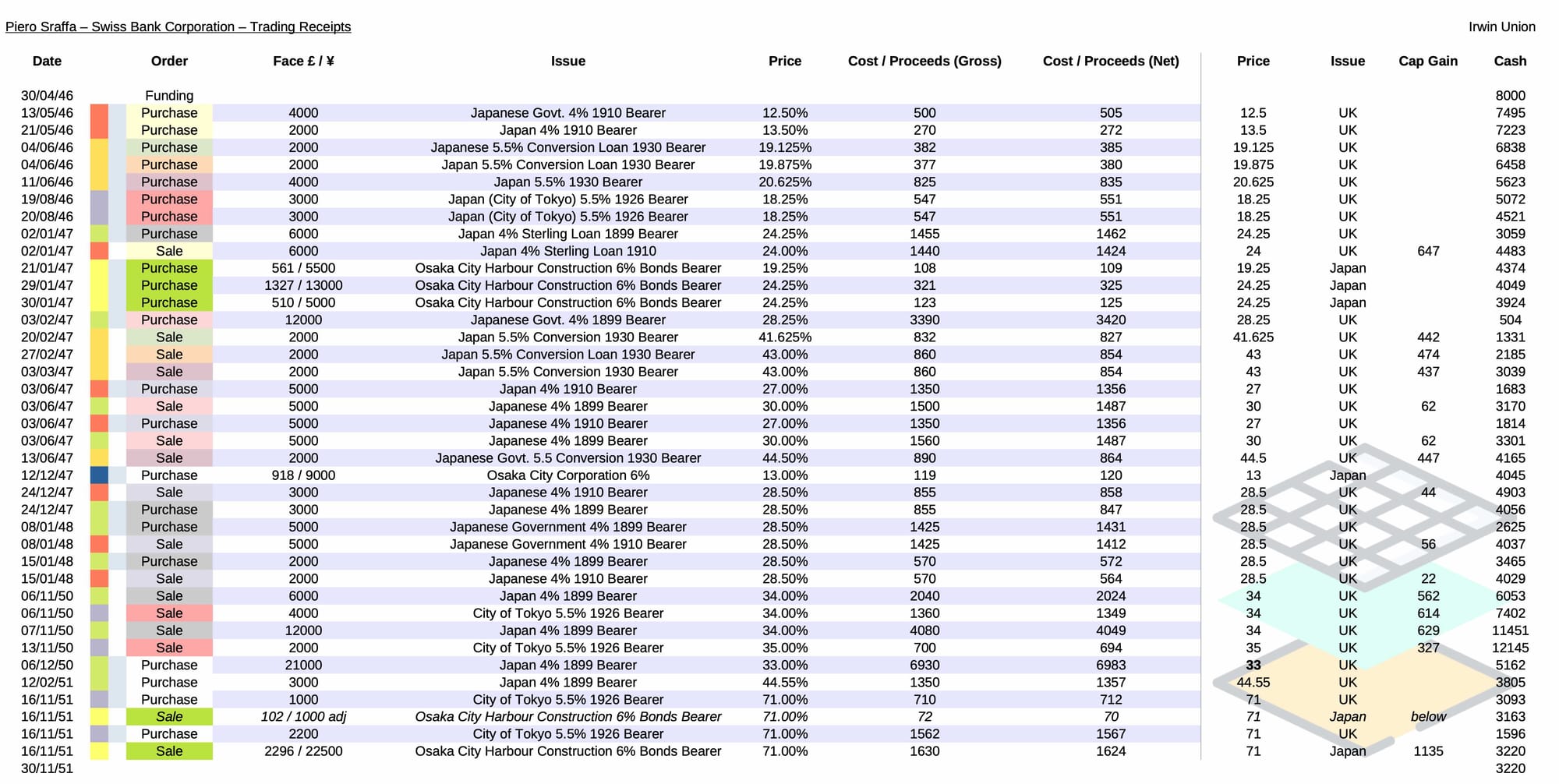

Among the items in Sraffa’s archive at Trinity College are two remarkable sets of papers.

The first is a series of trading receipts issued by the London branch of the Swiss Bank Corporation. These receipts run from 1946 to 1951 and cover Sraffa’s trading of Imperial Japanese Government Bonds, as well as some miscellaneous securities (City of Wilno, Poland at 3.25 of par and Estonian bonds at 6 of par, as well as some common stock.)

The second is a series of letters received by Sraffa from an unnamed Swiss organisation who custodied gold bullion for him.

It’s reasonable to conjecture that this was also the Swiss Bank Corporation, though it’s impossible to be sure as the letters are so discrete as to carry no letterhead or distinguishing detail of any kind. These letters give us an inventory of Sraffa's bullion holdings in Switzerland as of 1975 and broadly corroborate Stone's assertion that Sraffa swapped out of bonds into gold bullion.

From the set of trading receipts, we can, with only a few minor adjustments, build a chronology of Sraffa’s trading, and, thus, a simulated portfolio of his holdings.

This portfolio can then be priced using collected price data.

As of 1960, we can substitute the simulated portfolio of bonds for gold (as per Stone's account) and then continue to price the portfolio all the way through to 1983.

I first collected monthly price data for the period from 1946 to 1951 (the period in which Sraffa was actively trading) and six monthly data from 1929 to 1960.

With this in hand, we can begin to unravel the question of how and what Sraffa accomplished.

Sraffa’s trading receipts show that between 1946 and 1951, he traded quite frequently, realising capital gains and recycling his proceeds into other Japanese issues.

In late 1951, Sraffa ceased his trading. From here, for the purposes of simulating his record, we assume that the portfolio remained static until 1960.

Sraffa's final trades consolidate his holdings into the 1899 bond. This issue bore one of the earliest maturity dates.

There are some things to note about the above table.

I have calculated a hypothetical cash balance to run alongside the account. I assume a starting account balance of £8000 and allow the account balance to be debited and credited with each trade.

This is not ideal, as the lowest balance that can accomodate all of Sraffa’s trades produces a quite high average cash balance of around £4000; almost half of the simulated account. This is unwieldy, but a necessary simplification. In reality, it’s unlikely that he operated in this way. Instead, it seems that he added and removed funds from the account at different times.

We will return to this issue later in the piece and model the account with a line of credit so as to produce an average cash balance approximating zero.

Sraffa also made purchases of Yen denominated Osaka City loans. There was no pricing data available for these bonds and so, as necessary, they are simply marked at cost. Thankfully, they were largely liquidated before the account became dormant.

The final point to note is that in the original trading record, there are more sales of Osaka City Harbour bonds than purchases. This was remedied by simply adjusting out the surplus sales value from the sale transaction noted as adjusted. The amount concerned is immaterial.

Above, find monthly price charts for each of the loans for the period in which Sraffa was actively trading.

Collected price data was used to construct a portfolio consisting of cash and securities for the years in which Sraffa actively traded.

Below, find the simulated account balance and composition.

One can get a sense of the extreme valuation of the loans during this period by contrasting the market price of each with their cumulative defaulted coupons.

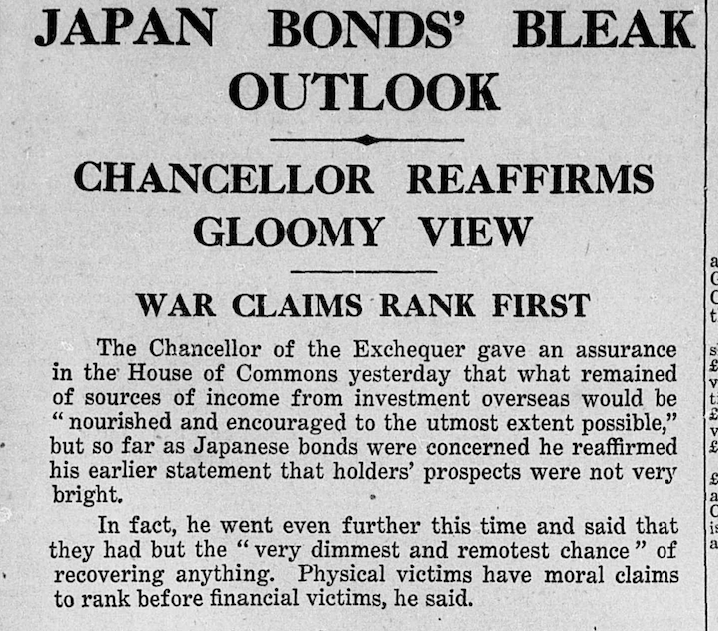

On the 9th of March, 1946, as Sraffa was likely contemplating his first purchases, the Financial Times ran a front page story titled Japan Bonds’ Bleak Outlook: Chancellor Reaffirms Gloomy View. The article reported on comments made by the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the House of Commons the previous day, wherein he stated that:

Following the Chancellor's remarks, the bonds sold off by approximately 20%.

Reading the financial papers of the time, one finds a veritable feast of views on the Japanese loans expressed in articles, opinion pieces and letters to the editor.

Indeed, in particular, letters to the editor functioned as a rudimentary clearinghouse for opinion and query. It is not a stretch to compare these exchanges to those that happen on message boards and social media platforms today.

The full record of these exchanges is too voluminous to excerpt in full. However, it is also so information dense that it forms a vital part of any study of the securities.

We learn some extraordinary facts from these articles and letters. For instance, as early as late 1946 thru January 1947, it was stated that interest on the defaulted bonds had been paid into sinking funds during the war.

One stock which tended to be overlooked when the market was active was the Tokyo Five Percent, 1912. Like Japanese Government Stocks, the interest has been set aside for bondholders in Tokyo throughout the period of the war and after, and Japanese nationals have been paid.

Any question of transfer to British bondholders awaits the signing of the Peace Treaty and the unfreezing of the yen-sterling exchange; the latter process can hardly be a quick one.

Japanese Bonds Speculation - Lex - Financial Times - 27/1/47We also learn that the cost of making British bondholders whole was relatively de minimis. This is because Japanese citizens, for reasons not apparent, owned most of the sterling issues. Japanese citizens were compulsorily converted into Yen denominated bonds in 1943, presumably due to strains on Japan's foreign exchange balances. This act left only the rump holdings of foreign owners intact.

A correspondent has lately received a cable from the Far East which has bearing on my note of yesterday on Japanese bonds. The cable reads as follows:

“Japanese Sterling Bonds interest paid all Japanese holders in Japan at former rates of exchange until March, 1942. Foreign nationals in Japan paid interest into special custody account. After March, 1943, Japanese owned compulsorily converted into yen bonds. No payments made of interest against unconverted bonds, but still being made on converted.”

That puts the position in a nutshell. Whatever the peace treaty may have to say on the matter, it is a fact, as is pointed out by my correspondent, that the default in interest due to British and Allied holders of Japanese sterling bonds not resident in Japan would not need a large sum to wipe out, as the Japanese always held the larger part of the sterling bonds. Lex

Japanese Post Script - Lex - Financial Times - 28/1/47We also learn of Japan's wish to join the United Nations and apply for membership of the IMF.

[...] 6) The goodwill of the Japanese since the end of hostilities, and the expressed desire of the Japanese Government to join the United Nations as soon as permissible after the signing of the Peace Treaty. An intention to apply for membership to the International Monetary Fund once the Peace Treaty has been signed has also been indicated.

Letters to the Editor - Financial Times - 19/4/47In the following letter, the author, a former resident of Japan, argues that the settlement of the debt would allow Japan to reestablish herself with foreign lenders at negligible cost.

Having spent several years in the service of the Japanese Government and having always kept in close touch with financial circles in that country, I have no hesitation in endorsing the view expressed by one of your readers a few weeks ago, namely, that the bonds in question are the best three-year lock-up on the market to-day, or as “Lex” remarked in your issue dated 2nd January: “If I were asked to name a good speculative long-shot for 1947, I think Japanese bonds would be as strong a starter as any.”

[...] Finally, the amount of Japan’s foreign indebtedness is infinitesimal, and the Government is fully alive to the fact that by meeting its commitments it is reestablishing its financial credits abroad at a very small cost.

Japan Bonds and ReparationsLetter to the Editor - Financial Times - 21/5/47

And then, on the 23rd of December, 1947, there is what can only be described as an extraordinary letter from William Teeling, a member of the House of Commons. This letter is excerpted in full.

Sir, -There has been much comment in your paper and elsewhere recently on the widening interest in all Japanese loans. Yesterday (Friday) afternoon I told a number of business men in the City interested in Japan what I know about these loans, and I feel that it is only fair that everyone should know, since contact with Japan and the Japanese is so difficult.

I have just returned as a member of a Parliamentary delegation which spent six weeks in the Far East, and while in Tokyo I made it my business to inquire about these loans which interest so many people here.

The Finance Minister in the present Japanese Coalition Cabinet told me that all interest accrued on the Japanese bonds would definitely be paid when peace with America has been signed. He could not say yet at what rate, but it would definitely not be at the rate when war broke out. He added that even during the war bondholders in Switzerland for certain loans were paid and he assured me that money has all the time been set aside in Tokyo for this purpose.

This was confirmed to me at a later meeting with heads of Japanese business firms and banks at which meeting the Foreign Secretary, Mr. Ashida, was also present. Mr. Ashida explained to me that new loans from America were essential and therefore Japan must keep up her reputation for meeting her debts and would pay off her earlier loans.

Reparations officials confirmed that the sums outstanding are small and could be repaid. The American officials concerned told me that a rate for the repayment of all debts will shortly be fixed and will definitely take into account the present depreciation of the yen.

But when will peace be signed? I only know that America was waiting for the recent Four Power Conference to break down before going ahead on a separate peace with Japan, and Great Britain will reluctantly support her as it is the only solution, but it will mean the strengthening of Japan and that means more loans.

William Teeling. House of Commons, S.W.1.

Letters to the Editor - Financial Times - 23/12/47And again, on the 8th of January, 1948, we find another letter from William Teeling, clarifying and expanding on his prior letter.

Sir,-As I am abroad I have not been able to answer before the letter published from “A Former Resident” on the subject of the Japanese Loans.

He asks why I accepted certain statements “without demur.” Quite frankly, I was not in Japan to negotiate nor to argue over details of any one problem. I was there to get as general an impression as I could in six weeks of the Japanese position as a whole.

I feel that Japanese bondholders should definitely make detailed inquiries for themselves either through the Council of Foreign Bondholders or, say, through the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank representative, who is already in Tokyo.

But they must remember that the Japanese Government is not yet an independent Government. Indeed, before the treaty has been signed there may well be another Government in power; but this new Government is likely to be more to the Right than to the Left and its probable leaders are still more friendly disposed towards Great Britain and still more likely to do all in their power to see that no bondholder suffers.

As regards Swiss holders, my impression was that the Finance Minister was referring to certain bonds placed in Switzerland, whether as a separate loan or not I am unaware, but surely bondholders or banks could easily find out what was the procedure?

I only discussed the loans with the Finance Minister at a luncheon given us by the Cabinet, but my later discussion with the Foreign Minister and business leaders was far more detailed. The Foreign Minister said: “You can tell your holders of the Japanese loans that they will not suffer in any way. If you want to make more, I should buy them now.” Others pointed out that Japan must have fresh loans and that to have them she wishes to have a completely clean financial slate.

I agree that the Finance Minister’s statement sounds less certain. But it must be remembered that he was speaking about many other debts as well during my conversation and may easily have forgotten that these debts are repayable in sterling. I certainly did.

I must, however, say that I came away from this and all such conversations with the Japanese convinced that they are determined to do whatever they had undertaken to do.

When I spoke to the Americans and referred to “rate . . . taking into account the present depreciation of the yen,” we were discussing repayment of all debts, including money owed in 1940 by Japanese to British and other business houses.

In my previous letter I particularly mentioned the statement “after the Peace Treaty with America has been signed” because (a) everyone feels that some sort of American Treaty will be pushed through this year no matter what happens, and (b) the Japanese wanted to stress that this is not a matter of what is decided in the Peace Treaty about reparations, this is an honourable debt which Japan will repay no matter what conditions are imposed on her, after she has again become a free nation, which she believes will be this year. This, therefore, has nothing to do with Mr. Dalton’s famous statement, as our chancellor could not prevent the Japanese repaying after a treaty.

Here may I refer to a comment by “Lex” on the same subject on 29th December. He wonders if Japan will be able to pay, if she will have the raw materials to make the goods to sell abroad and if there is a market. Already in the last quarter she has sold in the East more cotton piece-goods than the whole export sale from Yorkshire and Lancashire for the same period; she has recently signed - through S.C.A.P. - a second agreement with Russia to send to the U.S.S.R. machinery and locomotives in return for much needed coal; she has more silk than she knows what to do with and, like other countries, is only waiting for prices to come down to sell to them. America will see to her yen problem and India will help her in shipping. Lastly, experts from Britain consider that within five years she will once again be our greatest rival in the textile industry.

I hope that these points have answered “A Former Resident.” He must remember that this was the first message the Japanese have been able to give other than to our Embassy, to anything like an official or semi-official person. I doubt if they would have said what they did say lightly.

I doubt if anything more definite can be expected for the moment, but bondholders should make sure that their case is well understood in the right quarters, as peace terms are now being drawn up and the reparations committee is sitting regularly - its decisions should soon be reached.

William Teeling

Letters to the Editor - Financial Times - 8/1/48On the 23rd of August, 1949, we learn that Japan's total external debt was then $323mm USD with approximately $80mm USD of unpaid interest thereon. We also learn that British claims totalled approximately £62mm GBP.

Kaneschichi Masuda, Japanese chief Cabinet Secretary, said here today that he was unable to reveal any practical plans whereby Japans foreign bond commitments could be met.

[...]

He said that $323m. worth of bonds were held by foreigners, on which $80m. in interest had accumulated. British subsribers held about £62m. of this amount.

Japan and Bond Repayment - Financial Times - 23/8/49However, it was not so cut and dried. By 1951, the mood had soured, and the question of reparations, long simmering, had become acute. In April, Teeling again wrote to the Times, this time expressing concern about the lack of progress and the various possible outcomes for British bondholders.

At question was whether reparations would rank ahead of foreign bondholders, and whether reparations might exhaust Japan's capacity to make foreign bondholders whole, irrespective of her desire to do so.

Then, on the 13th of August, news of formal recognition by the Japanese Government of her prewar debts was published in the Financial Times.

Japan will not be restricted milatarily, politically or economically under the draft peace treaty published yesterday by Britain and the United States.

Japan affirms its liability for the pre-war external debt of the Japanese State, and for debts of corporate bodies subsequently declared to be liabilities of the Japanese State, and expresses its intention to enter on negotiations at an early date with its creditors with respect to the resumption of payments on those debts.

It will facilitate negotiations in respect to private pre-war claims and obligations; and will facilitate the transfer of sums accordingly.

Japanese bonds were active on the London Stock Exchange yesterday. Prices rose sharply at the opening and were up to £5 higher at one time. Following publication of the terms of the draft treaty there was, however, considerable profit taking. As a result, closing prices well after hours were £4 below the best.

Japan Recognises Debt Liability; Prepared for Talks on Payments - Financial Times - 13/8/51The formal end of hostilities between Japan and the Allied powers came in September, 1951, with the signing of the Treaty of San Francisco. With the treaty formalised, Japan was now able to turn to the issue of settling her defaulted foreign obligations.

In March, 1952, the Financial Times reported that the Japanese Government was placing £20mm on deposit in London as a goodwill gesture.

The Treasury announces that the Japanese Foreign Exchange Control Board is arranging to deposit with the Bank of England £20m. as a token of good will towards the holders of Japanese sterling bonds.

The initiative for this move was taken by the Japanese Foreign Minister. When neccessary formalities have been completed, the sum will be deposited and will remain with the Bank of England for two years.

During that period, it will be available for any payments by Japan to her creditors in connection with a settlement of her sterling bond indebtedness.

Japan to Deposit £20m. in London - Financial Times - 29/3/52The front page of the 29 September issue of the Financial Times read Japan to Pay Full Interest Arrears, and detailed the terms agreed upon in New York.

After negotiations lasting nearly two and a half months, agreement has been reached in New York on the treatment of Japan's bonded debt to Britain and the United States. It is a settlement that goes a very long way to meeting British Claims. The service on outstanding issues is to be resumed forthwith. Interest arrears that have piled up since the Pearl Harbour affair brought Japan into the war are to be met in full, though at a time lag of ten years from the due dates. There is a similiar arrangment for the treatment of repayment obligations. Moreover, the currency clauses included in a number of the debts under discussion at the conference are to be substantially honoured. The Japanese have, in short, comitted themselves to do what they said they would do before the conference began.

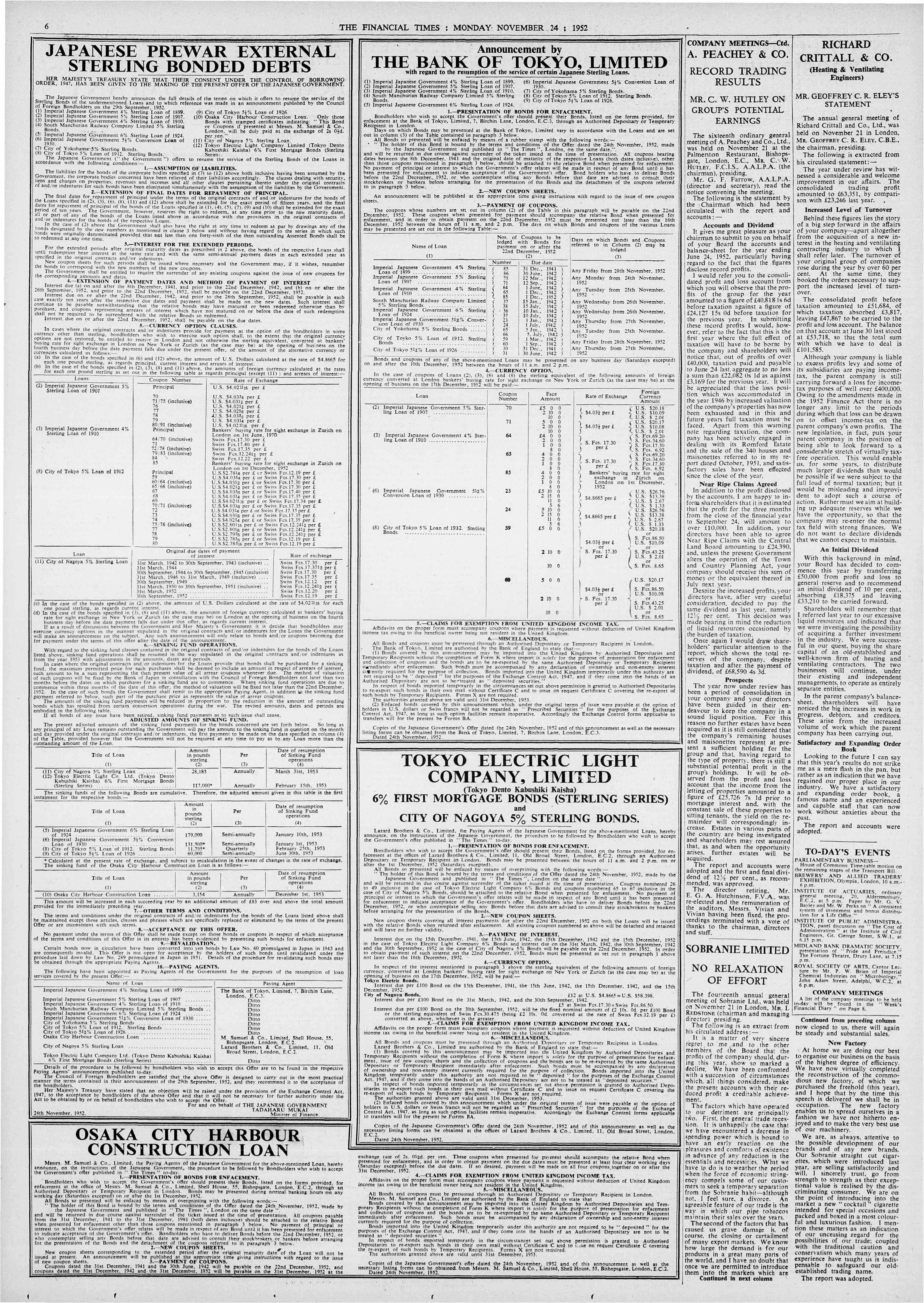

Contractual Terms - Financial Times - 29/9/52On the 24th of November, the Times published the full terms of the settlement.

Briefly, the terms provided for the extensions of maturities by ten and fifteen years, a catch up payment generally equal to a single coupon, and the amortisation of accumulated defaulted coupons. This was accomplished by paying one current and one defaulted coupon for each payment period until all defaulted coupons had been amortised. This, in effect, doubling the coupon of each bond for a discrete period.

Currency options (discussed further in Appendix A) were largely honoured in part or full.

| Issue | Original Maturity | Restructured Maturity |

|---|---|---|

| Japan 4% 1899 | 1/1/1954 | 1/1/1964 |

| Japan 4% 1910 | 1/6/1970 | 1/6/1985 |

| Japan 5% 1907 | 12/3/1947 | 12/3/1962 |

| Japan 6% 1924 | 10/7/1959 | 10/7/1969 |

| Japan 5.5% 1930 | 1/5/1965 | 1/5/1980 |

| Tokyo 5.5% 1926 | 31/12/1961 | 31/12/1971 |

| Tokyo 5% 1912 | 1/9/1952 | 1/9/1967 |

| Issue | Original Coupon | Restructured Coupon |

|---|---|---|

| Japan 4% 1899 | 4% | interim (£4); 8% from 31/12/52 through 30/06/1962; 4% thereafter |

| Japan 4% 1910 | 4% | interim (£6); 8% from 1/6/53 through 1/6/1962; 4% thereafter; currency option honoured in part |

| Japan 5% 1907 | 5% | * |

| Japan 6% 1924 | 6% | * |

| Japan 5.5% 1930 | 5.5% | interim (£5.5); 11% from 1/1/1953 through 1/7/1962; 5.5% thereafter; currency option honoured in full |

| Tokyo 5.5% 1926 | 5.5% | interim (£5.5); 11% from 31/12/52 through 30/6/1962; 5.5% thereafter |

| Tokyo 5% 1912 | 5% | * |

*- not modelled

With firm details of the restructuring of the loans, we can now model the post 1951 evolution of Sraffa's portfolio through to 1960. Below, I assume that Sraffa allowed his coupons to accumulate in cash, rather than reinvesting them.

With this account curve in hand, we can now model his swap to gold bullion in 1960.

At the end of 1960, Sraffa's simulated account had a value of £52,676.

At year end 1960, a kg of gold bullion cost £404.46. Thus, assuming no frictions, we find that Sraffa swapped his bonds and cash for ~ 130 kg of gold bullion.

With this, we can simulate the account through to 1983 and now have a complete account curve for the entire period.

According to these calculations, Sraffa compounded his initial simulated outlay of £8000 cash into £1,105,839, a multiple of 138 times, or 13.97% per annum over approximately 38 years.

With this simulated account curve in hand, we can now turn to Sraffa's correspondence with the Swiss bank who held his bullion. This correspondence acts as a valuable reality check on our calculations thus far.

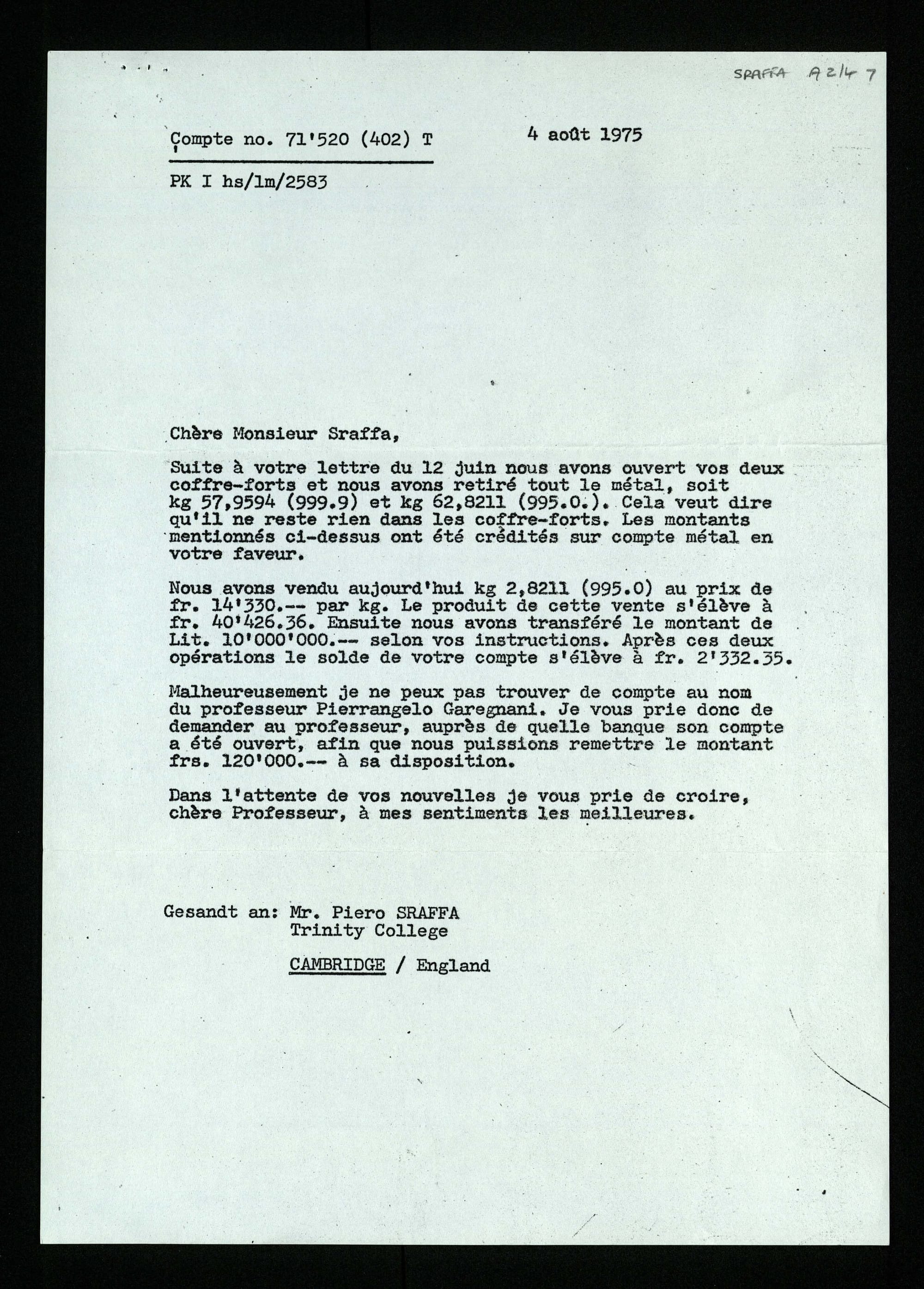

The above letter, from the 4th of August, 1975, reads:

Dear Mr Sraffa,

Following your letter of 12 June, we have opened your two safes and removed all the metal, i.e. kg 57.9594 (999.99) and kg 62.8211 (995.0). This means that there is nothing left in the safes. The amounts mentioned above have been credited to the metal account in your favour.

We have sold today kg 2,8211 (995.0) for fr. 14'330. -- per kg. The proceeds of this sale amount to fr. 40,426.36. We then transferred the amount of Lit. 10,000,000.-- in accordance with your instructions. After these two operations, the balance on your account amounted to fr. 2,332.35.

Unfortunately I cannot find an account in the name of Professor Pierrangelo Garagnani. I would therefore ask you to ask the professor which bank his account has been opened with, so that we can make the sum of frs. 120,000 available to him.

I look forward to hearing from you. Please accept, dear professor, the assurances of my highest consideration.From the above letter, we learn that as of August, 1975, Sraffa had gold bullion of ~ 120.78 kg under custody.

This is somewhat close to our simulated swap into gold bullion of 130 kg, but not quite perfect.

We also learn that in 1975 Sraffa had begun the process of liquidating his holdings, selling 2.8 kg of bullion and dispersing most of the proceeds.

Because there is no way to know how much he ultimately liquidated, and when, I opted to assume for the purposes of the prior simulated calculations that he simply held the entire 1960 bullion balance static. (i.e. I ignore the liquidation of 2.8 kg.)

That Sraffa chose to put a substantial portion of his net worth into bullion will likely strike the modern reader as strange. But Sraffa was a man who had studied the depredations of Italian post war inflation, as well as the devaluations of pegged currencies against bullion. Moreover, he was well acquainted with the problems and malfeasances of Italian banking.

To the end, Sraffa considered Italy his home and England his port in a storm. Switzerland likely emerged as a safe harbour between the two. That Sraffa chose to conduct all of his business through Swiss institutions underlines his apparent sensitivity to questions of legal domicile, political uncertainty and counterparty risk. An understandable sentiment given his fracas with Mussolini.

The above calculations are by no means perfect.

There is the weight discrepancy (120 kg of bullion in actuality vs 130 kg of bullion in our simulated account) and the issue of the ~ £4000 cash drag in the originally modelled trading account.

And what of our calculated rate of return? It almost certainly understates the true rate of return that Sraffa earned on his investments.

We can modify the calculations as follows:

We assume that Sraffa's account is funded with £4000, as this amount best matches Sraffa's trading, and delivers the most time without excess cash in his account. We further assume that Sraffa had access to a line of credit so as to accomodate the times when his cash balance goes negative.

We then debit and credit his trades as before.

We then model the account through to 1960. At year end, the account value totals £48,676.

Thus, from 1946 through 1960, this second simulated account curve compounds at 18.55% per annum.

We then swap the account into gold bullion, finding that £48,676 becomes, assuming no frictions, ~ 120 kg of bullion.

For the whole period, from 1946 to 1983, this second simulated account compounds at 15.84% per annum.

This might seem small a small difference versus the 13.97% we calculated earlier, but it produces a drastic difference in terms of MOIC. The second account is multiplied by 255.5 times, rather than the 138 of our first simulated account.

We return now to the beginning. Whilst nothing definitive can be said of Sraffa's record, we can conclusively show that he did in fact make the incredible investments that have long been speculated about. The evidence is ample that he was an active trader and owner of the London listed Imperial Japanese Government bonds.

We can be relatively sure of Stone's assertion that Sraffa swapped his bonds into gold, owing to the correspondence excerpted herein. We cannot be sure of the year, but the continuity of our second simulated account curve and Sraffa's documented bullion balance lends substantial credence to Stone's account.

Of Kaldor's history of Sraffa's activities, we find them to be broadly correct, though with some minor qualifications.

In our second calculation, we find that Sraffa's account grows from £4000 in 1946 to £48,676 in 1960. This is a multiple of 12, and a far cry from the 40 to 50 times that Kaldor asserts that Sraffa made on his bond purchases. Nonetheless, Sraffa very likely did multiply his outlay by hundreds of times over the full period to 1983.

Remarkably, we find in the financial press of the day the lineaments of an investment thesis complete with assurances from members of the Japanese government.

We cannot ever be truly sure of what Sraffa achieved, but we do have enough to construct two separate scenarios, each strongly suggesting that he earned a mid double digit return on his outlay for the better part of 40 years.

Though the calculations are crude and significant ambiguities remain, we might suggest that, assuming Sraffa continued to hold the substantial portion of his bullion through to 1983, he likely earned just shy of 16% over 38 years.

This, a record that surely places him amongst the most successful investors of the 20th century.

Further Reading

Appendix A - Total Return Series, 1945 - 1960 Including Currency Options

Of the bonds for which data was collected, both the 1930 and 1910 issues contained currency options that allowed their holders to take coupons and / or principal in foreign currency.

Intriguingly, the rates of exchange on these options were fixed, and so, as exchange rates moved, these currency options opened up the potential for arbitrage.

eg.

When issued, the 1930 loan allowed for payment of coupons and principal in GBP or USD at an exchange rate of 4.865 USD per GBP.

We can see from the below chart that this was the prevailing exchange rate at issuance. However, the pound subsequently weakened dramatically against the dollar. Such that, by the early 1950s, the rate had fallen to 2.80 USD per GBP.

Here lay the arbitrage.

The buyer could elect to take their coupons and principal in USD at the old rate (4.865 USD per GBP or 0.206 GBP per USD), and then convert them back to pounds at the new rate (2.80 USD per GBP or 0.357 GBP per USD).

In essence, turning 0.206 GBP into 0.357 GBP, a gain of 73.75%.

£1 -> $4.865

$4.865 -> £1.74

I modelled this arbitrage in two ways: In the first, I simply allow the coupons to accumulate in cash, and in the second, I reinvest the arbitraged coupons back into more of the underlying loan. Both methods are shown in the charts above.

If one studies the chart of the 1930 loan, they find that this bond in particular traded for far more than its GBP face value. This is because the market was alive to this arbitrage opportunity and priced the loan correctly at +/- 175% of GBP face value.

Of all the loans studied, the 1930 issue had the most dramatic returns.

Appendix B - Price Return Series, 1929 - 1960

Preferred Reference

Example:

Lonergan, S. "Off the Run: Piero Sraffa and Imperial Japanese Government Bonds" Irwin Union, 20 Feb. 2024, https://irwin-union.com/sraffa/

References

Piero Sraffa - Unorthodox Economist (1898 - 1983): A Biographical Essay, Jean-Pierre Potier, Routledge, 1991

Piero Sraffa 1898 - 1983, Nicholas Kaldor, Proceedings of the British Academy 71, 1985

How They Did It: Exceptional Stories of Great Investors, Murray Stahl, Horizon Asset Management, 2011

World War Two: A Short History, Norman Stone, Penguin, 2013

Papers of Piero Sraffa, Trinity College, University of Cambridge

Annual Report, Bank for International Settlements, Various Years

GOLDPMGBD229NLBM & USUKFXUKM, FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Accessed June 2021

Gold Price Data, London Bullion Market Association, Accessed June 2021

Gold Price Data, Chards, Accessed June 2021

Historical Price Data, The Financial Times, Accessed June 2021

Errata and Notes

9/12/24. Added Norman Stone reference previously omitted in error.

9/12/24. Revised text.